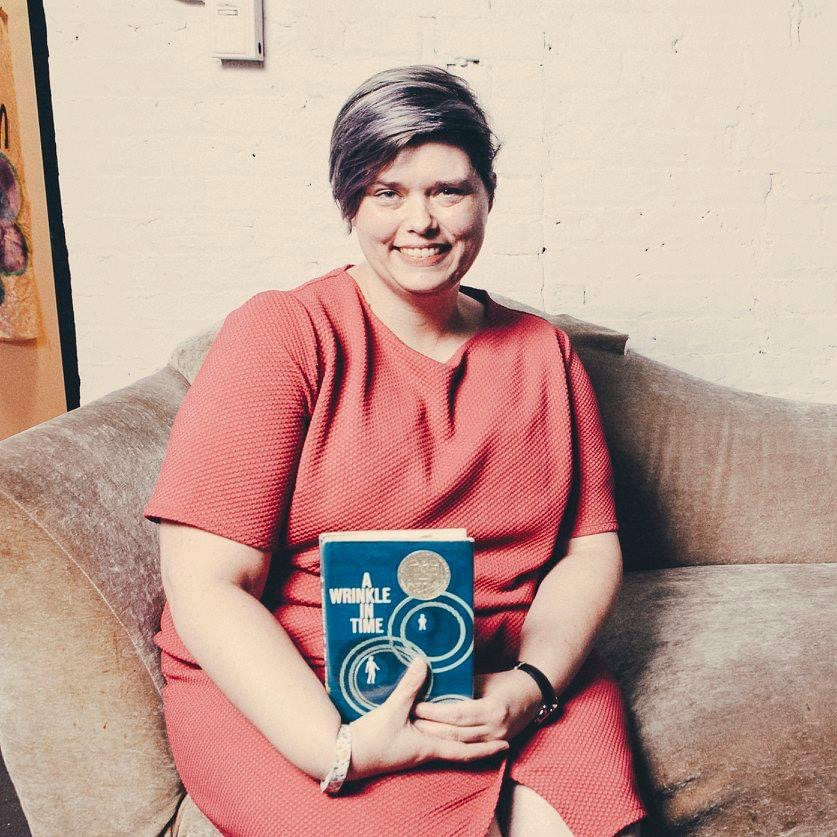

In college, for one of my literature classes, I had to write a paper on the novel Moby-Dick. Being the person I was, I waited and waited to decided on a topic, until it was the night before the paper was due, and in a frantic fever I churned out a paper about how writing a paper about Moby Dick was in a way my own personal white whale.1

I wish I still had that paper, but sadly, it was lost many moves ago. I do remember I got a decent grade on it, but my professor did comment something along the lines of, “You did basically nothing that I asked of you, but the resulting paper is so audacious and enjoyable to read, I can’t in good conscience fail you.”

The only other Melville work I’ve read is “Bartleby, the Scrivener,” which is, at its most basic, the story of a scrivener (copyist) who starts off at his new job working at a furious pace, but then over time begins to do less and less, eventually doing nothing, and saying “I would prefer not to” to every request made of him. Which, I totally get, because his boss is not great–he tolerates some really obnoxious behavior from the two other copyists in the office, and I think Bartleby is smart for wanting to assert some boundaries and saying “I would prefer not to” when asked to do repetitive, useless tasks that take him away from more important work.

Soon his boss realizes that Bartleby is actually living in the office, hardly moving or eating. Eventually his boss is so weirded out by this that he MOVES OFFICES ENTIRELY AND LEAVES BARTLEBY THERE for the next tenant to deal with. (??!!!??) (Honestly, though, I’ve worked in libraries where admin has gone to lengths almost as absurd to avoid having to actually deal with a personnel problem.) Spoilers, eventually Bartleby goes to prison and dies of starvation.

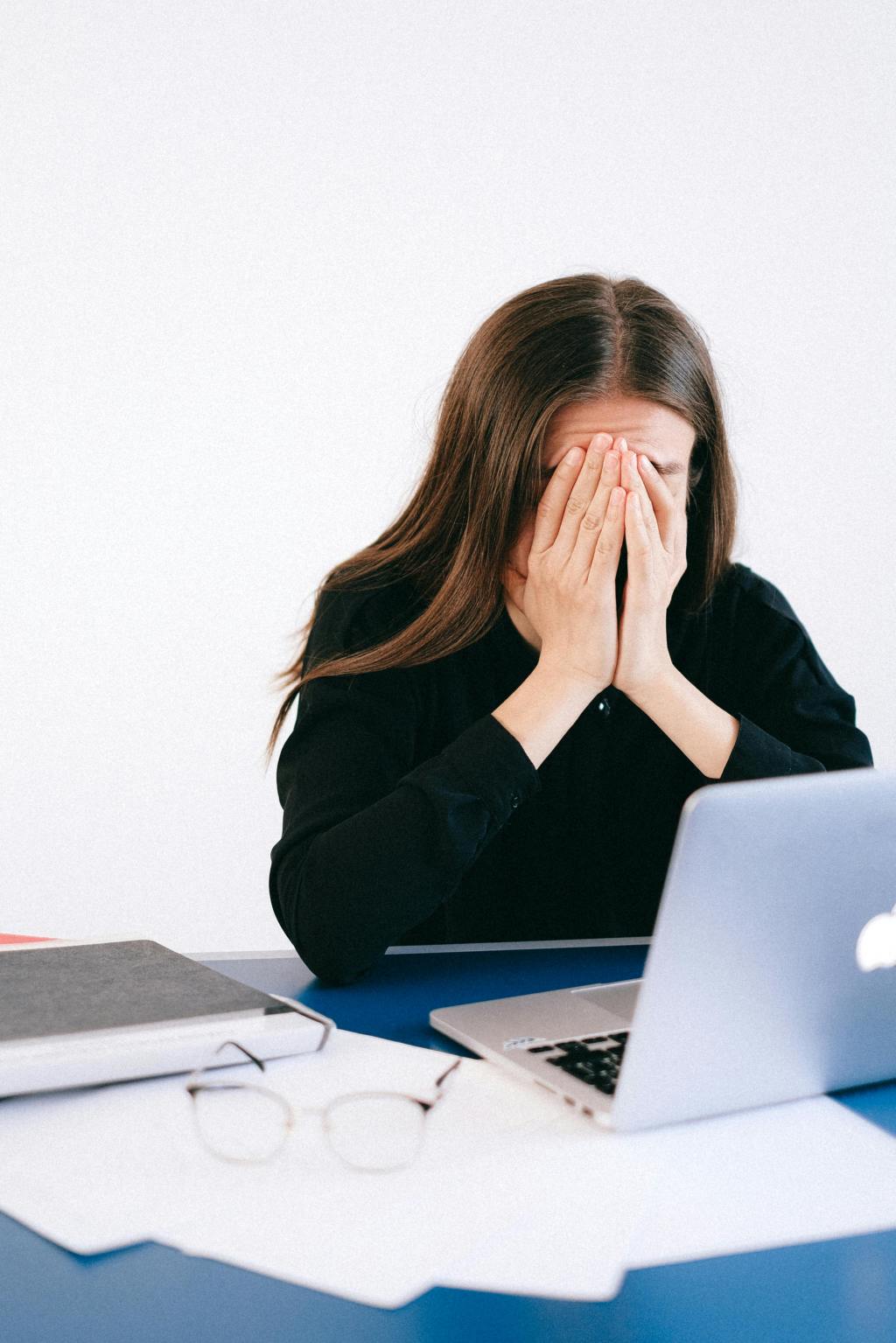

I think about Bartleby a lot when I think about my career in libraries. When I started out, I was so motivated, so excited, so ready to take on challenges and do good work. I believed in the mission of libraries and was excited to contribute to the bettering of communities through literacy and connection.

Like Bartleby, in the beginning, I was productive and enthusiastic. In one of my earliest jobs, I presented programs four out of five days, and usually multiple programs in a day– back to back storytimes in the morning and special programs in the afternoon. Each day was split between programs and working on the desk. Program prep, collection work, and almost every other task we did was done while on the desk. This type of multi-tasking happens quite often in libraries even though it’s been proven that multi-tasking doesn’t work. (And while everyone is bad at multi-tasking and, it’s yet another work expectation that’s harder for people with ADHD to do/pretend to do.) Trying to do any kind of deep work while being constantly interrupted is a recipe for mistakes and burnout, and that’s often what happens with library workers in these conditions.

As time went on and I worked in different roles at different organizations, things didn’t change much. There was almost always too much work to be done and not enough time or support to do it. The people with all the power and authority never seemed to want to do the right thing if it would be at all difficult. (Do people in high paying positions not realize that’s what the money’s for? You get paid more than everyone else PRECISELY because you are the one who ought to be dealing with the most difficult problems.) Everything felt bogged down by labyrinthine processes or needless dithering over the “right” decision.

Instead of being given time to do our work, we spent too much of our time in endless meetings with no agendas, outcomes, or action items. Instead of serving our core mission of providing accurate information, we kept shouting “We’re more than books!” even though what people wanted from us most were books.

Then came a presidential administration that was so anti-intellectual and pro-misinformation that it was effectively completely anti-library. It was around this time when for many librarians “I’d prefer not to” was turning into “I’d rather die.”

I know I’m not alone in this. I’ve been seeing so many excellent people leaving librarianship recently due to burnout, stress, and low pay, and even if they’re staying in the library field, they’re definitely looking for ways to make library work more sustainable and less harmful to workers.

This exodus, unfortunately, has been a long time coming. As I’ve been learning more about workplace burnout (which is probably just capitalism burnout at this point), one of the things that I’ve found most compelling is the aspect of moral injury, which, briefly, is when one is forced to work in an environment where they experience: lack of safety, both physical and psychological; excessive demands in terms of workload, often due to understaffing; and operational inefficiencies due to issues with workflows and administrative dysfunction. (Sound familiar?)

The framework linked is specifically about health care and public safety workers, but there are many commonalities between those professions and librarianship and how we’ve all been impacted by the events of the last eight or so years, so I think you’ll find that framework relevant and validating. Library work, like aspects of health care, has become politicized. What was once seen as a nonpartisan2 community good by most has become the target of baseless accusations by a very vocal minority. Yet most people3, especially caregivers of youth, still find librarians to be extremely trustworthy.

Yet so many library administrators don’t bother to trust their own employees. For years, library administrators have been contributing to burnout due to supporting their when situations became difficult or listening to front line workers when managers were making changes that would harm both workers and patrons4.

Then the pandemic and the rise in anti-intellectual sentiment came along to do even more damage to the morale of library workers, many of whom were already suffering due to being understaffed, underpaid, and undervalued by their employers. (Consider, also, this trauma being piled onto library workers already traumatized by personal trauma, generational trauma, existing mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety, and no wonder people are desperate to get out. Black librarians, queer librarians, and neurodivergent librarians are REALLY not okay.)

So why this disconnect? Why do the statistics say that our patrons and communities value and trust us, while our own organizations continually act in ways that say they don’t trust their staff? Why are so many library leaders afraid to let their communities know that the library staff that they often appreciate are not okay? Why don’t we do more to let our communities know when we need their support?

I think that oftentimes library leaders assume that if they keep anything remotely controversial quiet (book challenges, staff reorganizations that impact morale and the quality of public service, complaints about inclusive displays and programs, etc), then they minimize the chance that they’ll have to deal with any scrutiny from either their staff and the public. (See again: that’s what the money’s for).

I thought about this a lot when libraries in the Illinois area were getting hit by bomb threats. So many libraries posted closing notices on their websites and social media, but hardly any of them took the time to be vulnerable and to tell their communities the truth about what was happening. As Jensen points out in her excellent article, posted October 12, 2023:

Library workers and educators have been under attack for nearly three years, and while it is unfortunate to note that bomb threats aren’t new, their escalation over the last month demands attention and action. These should be nationwide headlines, but they are hardly making a blip in their own local media. This stochastic terrorism is not only shutting down public institutions, but surrounding the few public goods in terror for workers and for users — this is, of course, the point, and it should enrage every taxpayer who helps fund these institutions.

The weird insistence that library workers should have to just go about their work as though they are not under constant stress and emotional turmoil is baffling to me. Why should we be forced to hide our pain and our fear under a customer service smile? I think we’d all be better off if we could allow ourselves to say, “I’m having a hard time and I could use some grace.” We should being saying this, out loud and often, as individuals, as organizations, and as a profession. When even the most joyful librarian in the public eye right now had to leave library work due to the toll it was taking on his mental health, things are NOT good.

Sure, if you talk about these things openly, will some people gloat and agree? Will there be people in your community who do think the worst of you and assume ill intent in everything you do? Of course. That’s the world we live in now. But I believe that for every person who accuses the library of acting against the greater good, there will be many more who speak up for the library and stand in solidarity with the mission to provide equitable access to information for everyone. But how can we expect support when we don’t ever ask for help? At every level, we need to ask for help and make connections. We cannot continue to suffer in silence, and we shouldn’t have to.

I’ll leave you with some recommended reading, because recommending books is one of the reasons I went into librarianship: if you haven’t read Pet by Akwaeke Emezi yet, you need to. In it, Emezi quotes the poem “Paul Robeson” by Gwendolyn Brooks, and ever since I read those lines they’ve been seared on my heart:

[...] we are each other’s

harvest:

we are each other’s

business:

we are each other’s

magnitude and bond.

One of the main questions of the novel is “How do you save the world from monsters if no one will admit they exist?” But admitting the monsters exist is just the first step of making things better. Once that secret’s been acknowledged, it is not a problem to be solved by individuals, but rather by the community, by coming together and collaborating and supporting each other.

We need to admit what monsters exist in our profession, and start working to make things better, because I’d prefer not to keep pretending that everything’s fine and that we don’t need help.

How about you?

- I now know I have ADHD and need the pressure of a looming deadline to accomplish most things. It explains so much of my youth. ↩︎

- Libraries are not, should not, and never have been neutral. Seriously. I mean it. ↩︎

- This data is from 2017; I would love to find something more recent. I’m sure the needle has moved. Much like nurses have lost ground over the past few years, and teachers, I‘d be surprised if the environment of the last eight years didn’t change how people feel about libarians. ↩︎

- Joking about killing people who work for you is never funny. And dismantling a department even though every single employee is trying to tell you all the ways in which it won’t work just so you and two of your white male colleagues can pitch a conference presentation with a shocking name is not how ethical or caring leaders behave. ↩︎

Leave a comment